Around three decades before I first stepped into Oddingley parish in 2008, a local GP named Gael Turnbull did the very same. And for some years afterwards he walked the twisting country roads, he took snap shots of the Netherwood barn and the cottages that clung to the fringes of Church Lane, and he delved deep into the story of the Oddingley murders.

At home, pages of notes flowed from his pen until notebook upon notebook piled up about him, all crammed with dates, tables, sketches, maps, blood lines. I cannot know for exactly how long his labours continued, but I do know that when he finished his inquiries he had completed a manuscript entitled A Dirty Job For Captain Evans.

I’ve a photograph of Gael Turnbull before me now. It shows a man with silver hair, broad glasses, a thin face and a mischievous smile. His story of the murders was never published, instead it was deposited along with his notes and letters into the archives of the Worcester Records Office in two bequests: one in the 1990s and another following his death in 2004.

But the murders were far from the only topic to catch his imagination. I subsequently learnt that he was a poet with an international reputation – well known to Burroughs and Ginsberg – and, in addition, ‘a translator, lyricist, prose-poem writer, kinetic sculptor, morris dancer and book maker. He was also a doctor and anaesthesiologist; conscientious and intuitive in his trade.’

You can hardly hope to read a more colourful biography of a man than that contained in Turnbull’s obituary, published in the Independent. I’ll quote just one paragraph from it, a paragraph that neatly portrays a life of energy and intellectual curiosity all displayed in the course of just a single day:

‘Gael Turnbull gave his final reading on a library roof in bright sunlight this May at Exeter’s tEXt festival. He had boarded the train loaded with kinetic sculpture and Zola’s La Bête humaine to read. In Devon in the next 24 hours he visited Exbourne Church to peruse its tithe map, drank in the Scottish poet Seán Rafferty’s pub and saw his old house, whittled a wooden dagger, checked my ill son’s temperature, recited “Sir Patrick Spens” by heart and found a cob wall full of doves. The next day, thronged by people, he read participatory kinetic poems, and left for St Ives.’

I discovered Turnbull’s files on the Oddingley case about two years ago as I was beginning the edits for Damn His Blood. It was one of those unexpected and exciting discoveries that belong particularly to historical research. Sifting the papers it was clear we had followed the same threads, reached many of the same conclusions and puzzled over many of the same ambiguities. In several places he surpassed me, and to him must go credit for tracing Richard Heming’s opaque ancestry to its source – something that I write about in a chapter entitled The Man in the Long Blue Coat.

As a non-fiction writer, you’re rarely on your own ground. In all but the most obscure, individualistic or recent cases you’re following paths that other writers have blazed, trying to make the story your own. This can, of course, result in rivalry but it can also give rise to a sense of fellowship, as there is among Dickensians who study Dickens or Henricans who explore the reign of King Henry VIII. And if there is to be a collective nouns for those who’ve studied the Oddingley case, then what better title that Oddingleyians?

So this post is intended to thank Gael Turnbull and to remind people of his work. I think it’s best to end with this quote from his friend, the British poet Roy Fisher, I can’t better it:

‘Of all my lost friends he is the least dead. The unique pace of his mind, sometimes troubled, always curious, seems still to be keeping us company somewhere just out of reach.’

—

Gael Turnbull (1928-2004) – Nicholas Johnson’s Independent Obituary, Guardian Obituary, Collected Works

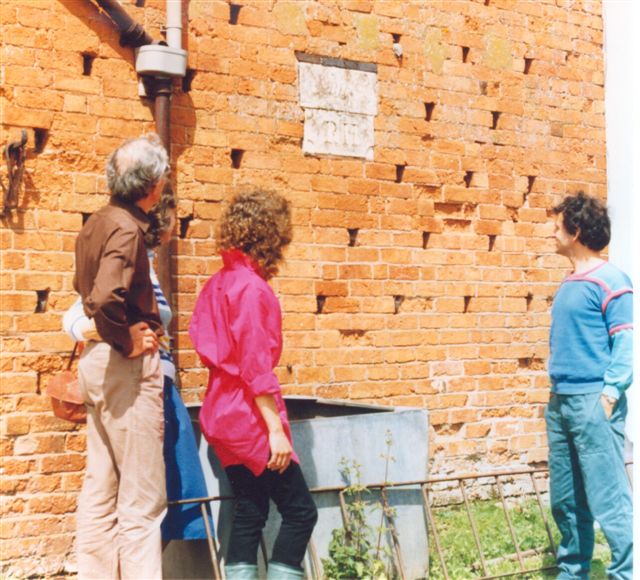

(Gael Turnbull and friends outside Netherwood Farm, Oddingley, looking up at the murder plaque.)

Photos kindly supplied by Jill Turnbull.