Little Green Bag

On the second anniversary of the Storming of the Bastille, 14 July 1791, a rampaging mob descended on the Birmingham home of Joseph Priestley with the aim of roasting him alive. Among King & Country patriots, Priestley was infamous. He was one of a dangerous set of idealistic dissenters, liable to spark a revolution in Britain that was every bit as horrible as the French one they had read about in the newspapers. The rioters had decided to anticipate Priestley with violence of their own.

So begins Mike Jay’s book, The Atmosphere of Heaven, which vividly recalls the Priestley Riots. Priestley himself is a well known character. He was the first to isolate oxygen in 1774 (a gas in which candles burned brighter and mice lived longer than in common air) but when the political climate turned hostile in the 1790s he fled, first to Hackney in London and later to liberal America where he could pursue his experiments and cherish his ideals in safety. Behind him he left his smouldering Birmingham home and his valuable and unique instruments. By the end of the prologue Priestley is gone, but the abrasive English society that he left behind remains – emptied and primed for the appearance of a new character.

In 1791 Thomas Beddoes was 31 years-old. He was a free-thinking polymath, a reader in chemistry at Oxford University, a subject he could pursue in Latin, Greek, French, Spanish or Italian. In addition, Beddoes was something of a botanist, something of a geologist, entwined in politics, a prodigious writer of pamphlets and – in one instance – an instructive novel. He strides into Jay’s narrative – a fat man, short and wheezing – but brimming with ideas as he rambles across the Cornish countryside. Beddoes is an admirable hero, forever distracted by dreams of a better society. The main subject of Jay’s book is Beddoes’ memorable project – his Pneumatic Institute in Bristol.

The Pneumatic Institute is a curious, if not ultimately successful, moment in the long history of medicine. Its aim was to discover cures for consumption, palsy and the other evil diseases of the age by treating the stricken and ‘drooping’ patients that were admitted with various gasses. After years of scrabbling around for funding and support, the Institute finally opened in 1799 and Jay’s beautifully-written narrative documents the highs and lows of the project that was, ultimately, a failure – although one marked by several notable achievements.

The Atmosphere of Heaven is both a group and cross-cultural biography that deals with a wide-range of themes. There is the revolutionary ferment in British society in the 1790s, Pitt the Younger’s fight against free speech, the state of medicine, science and philosophy. Bristol, the setting for the Pneumatic Institute, emerges as a delicate liberal foothole during this time, a haven for both enlightened and romantic souls – among them Robert Southey, Tom Wedgwood and Samuel Coleridge. The most notable phase in the story, however, begins with the opening of the Institute in 1799 and the emergence of Humphry Davy – ‘the extraordinary person from Penzance.’

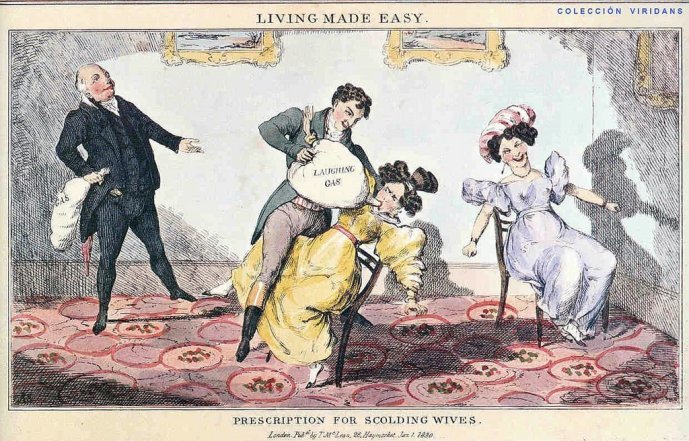

Davy’s isolation of nitrous oxide (later known as laughing gas) and his self-experimentation results in the book’s most vibrant chapter, Wild Gas. In a memorable series of reports, Davy carefully recorded the effects of the gas – which was, in turn, tasted by several members of the poetic circle. When Southey tried the ‘little green bag’ for the first time he felt little more than a slight dizziness. On the second helping, the results were more noteworthy:

Southey’s reaction did not disappoint. He felt the initial dizziness that he remembered, a moment of vertigo as he sucked the last of the gas into his lungs; then, as Davy removed it, he let out a profound and involuntary laugh, accompanied by a thrill that diffused right through to his toes and fingertips ‘a sensation perfectly new and delightful.’ As it ebbed, it left his feeling refreshed and renewed, and for the rest of the day he ‘imagined that my taste and hearing were more than commonly quick.’ In summary he offered the epigram that ‘the atmosphere of the highest of all possible heavens must be composed of this gas.’ Away from the laboratory he was more exhuberant still. ‘O Tom, such a gas has Davy discovered, the gaseous oxyd.’ He wrote immediately to his brother. ‘O Tom, I have had some, it made me tingle in every toe and tinger-tip!’ Davy has actually invented a new pleasure for which language has no name. O Tom, I am going for more this evening, it makes one strong and happy, so gloriously happy! O! Excellent air-bag!’

The Atmosphere of Heaven is a fascinating step backwards into an exhilarating age of scientific debate and progress. There’s a gentle overlap with Richard Holmes’ The Age of Wonder and Jenny Uglow’s The Lunar Men and it continues a strand of history championed by Roy Porter. But Mike Jay has cut a new path of his own. It’s satisfying to see such a likeable and well-intentioned character as Beddoes restored to life in a book that sparkles with life.

—

Image Credit: No Laughing Matter on Flickr