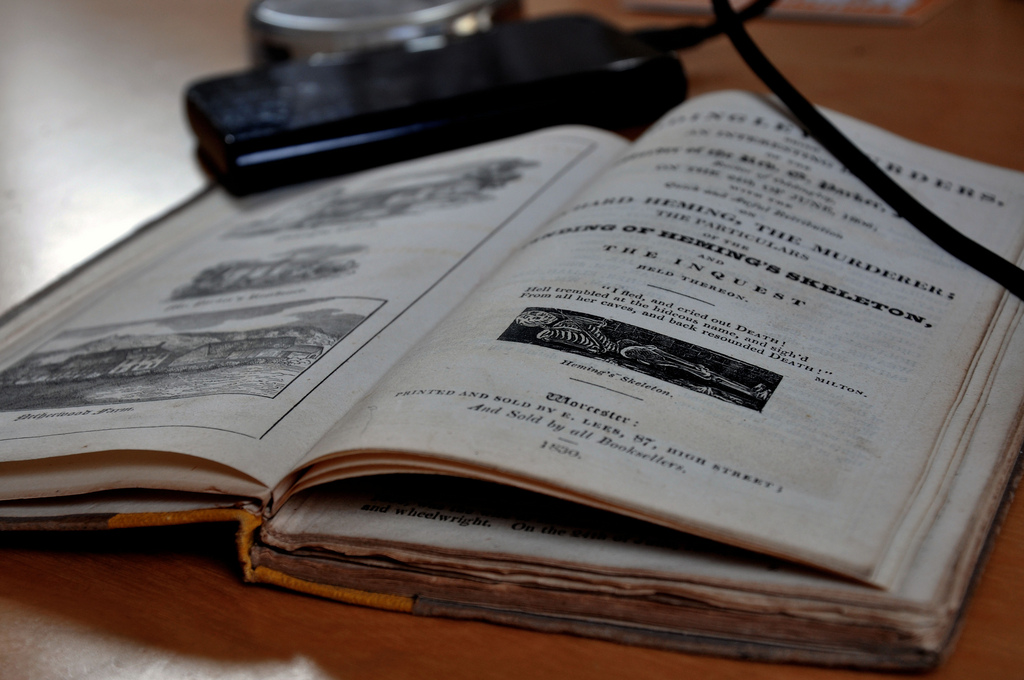

For World Book Day, I thought that I’d put up a photo of one of the most interesting books I own. It’s a collection of three chapbooks, all of them printed in Worcester during the spring of 1830.

They are the work of the city’s two most successful contemporary printers, Edwin Lees and Thomas Eaton, and they document the public inquiry and subsequent trial that concluded the story of the Oddingley murders.

Almost two hundred years on, the chapbooks are still in a good condition. Though their paper feels coarse and brittle, the ink has barely faded and, if they smell of anything at all, it is only the faintest hint of old-fashioned dust – of the variety that a knight of the realm might keep on his grand piano.

I like the chapbooks not only for their content, which has consumed my evenings for the past few years, but also because they are tangible objects that give me a link with history. It’s interesting to think they would have probably been produced amid a forest of levers on one of Friedrich Koenig’s iron printing presses, then carted away to the booksellers in bound parcels where they would have been sold by men in tall hats with mutton-chop whiskers.

From then on, I can only wonder how the chapbooks survived through history. They were there equally for the deaths of George IV and Princess Diana. When war broke out in Europe in late summer of 1914, they were already more than 80 years old. In these years I wonder who owned the chapbooks? Were they kept together as a set, or reunited at some point later on? Were they hidden in a box, paraded on a shelf or kept in a bedside drawer?

Exploring the narrative history of objects is a popular literary theme at the moment, but I can’t help thinking that history is captured most strongly of all, in old books like these.