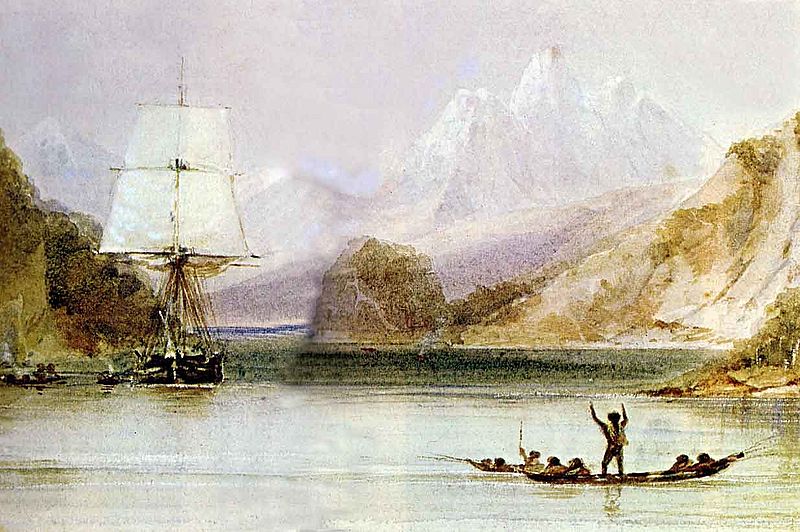

(Watercolour of HMS Beagle by Conrad Martens)

On 29 August 1831 twenty two year old Charles Darwin, freshly graduated from Cambridge University and poised to begin a life as a clergyman, received a letter from Professor George Peacock. It contained an incredible offer. Peacock told Darwin that a naval captain, Captain Robert FitzRoy, was seeking a philosophic companion for a voyage to the south seas. Peacock wondered whether Darwin would be interested.

The subsequent Voyage of the Beagle (1831-1836), would become one of the most celebrated of the century and, perhaps, in all history. It was the voyage that shaped Dawin’s mind, fixing him on a course that would end with the publication of his On the Origin of Species three decades later.

But Darwin very nearly didn’t go.

When he received Professor Peacock’s letter in August 1831 his father, a towering influence, set out a list of eight objections. Charles was left to mull these over on a visit to see his Uncle Jos.

The two men tackled his father objections systematically.

(Father’s objection number one) Disreputable to my character as a Clergyman hereafter.

(Uncle Jos’ reply) I should not think it would be in any degree disreputable to his character as a clergyman. I should on the contrary think the offer honourable to him, and the pursuit of Natural History, though certainly not professional, it is very suitable to a Clergyman.

(Father’s objection number two) A wild scheme.

(Uncle Jos’ reply) I hardly known how to meet this objection, but he would have definite objects upon which to employ himself and might acquire and strengthen, habits of application, and I should think would be as likely to do so in any way in which he is likely to pass the next two years at home.

(Father’s objection number three) That they must have offered to many others before me, the place of Naturalist.

(Uncle Jos’ reply) The notion did not occur to me in reading the letters & on reading them again with that object in mind I see no ground for it.

(Father’s objection number four) And from its not being accepted there must be some serious objection to the vessel or expedition.

(Uncle Jos’ reply) I cannot conceive that the Admiralty would send out a bad vessel on such a service. As to objections to the expedition, they will differ in each man’s case & nothing would, I think, be inferred in Charles’ case if it were known that others had objected.

(Father’s objection number five) That I should never settle down to a steady life hereafter.

(Uncle Jos’ reply) You are a much better judge of Charles’ character than I can be. If, on comparing this mode of spending the next two years, with the way in which he will probably spend them if he does not accept this offer, you think him more likely to be rendered unsteady & unable to settle, it is undoubtedly a weighty objection – Is it not the case that sailors are prone to settle in domestic and quiet habits?

(Father’s objection number six) That my accommodations would be most uncomfortable.

(Uncle Jos’ reply) I can form no opinion on this further than that, if appointed by the Admiralty, he will have a claim to be as well accommodated as the vessel will allow.

(Father’s objection number seven) That you should considered it again as changing my profession.

(Uncle Jos’ reply) If I saw Charles now absorbed in professional studies I should probably think it would not be advisable to interrupt them, but this is not, and I think will not be, the case with him. His present pursuit of knowledge is in the same track as he would have to follow in the expedition.

(Father’s objection number eight) That it would be a useless undertaking.

(Uncle Jos’ reply) The undertaking would be useless as regards his profession, but looking upon him as a man of enlarged curiosity, it affords him such an opportunity of seeing men and things as happens to few.

Before Charles met with his Uncle Jos his father had promised him that, ‘If you can find any man of common sense who advises you to go, I will give my consent.’ And on Charles’ return home he found that his father’s resolve had softened. Within a few months he was in Plymouth and ready to sail into history.

(More Historical Miscellany here.)